BACCM Overview - The Core Concepts that form Business Analysis - Core Concept Model

1.0 BACCM Overview – The Core Concepts

Six Core Concepts form the foundation of Business Analysis: change, need, solution, context, stakeholder, and value. The Business Analysis Core Concept Model™ (BACCM™) describes the relationships among these Core Concepts in a dynamic conceptual system. All the concepts are equally necessary: there is no 'prime' concept, and they are all defined by the other Core Concepts. Because of this, no one Core Concept can be fully understood until all six are understood.

If you haven't played the Core Concept Random Walk game from last time, please try it now. It's a very fast exercise, and you'll find your insights are more nuanced during this discussion.

Last time we talked about the origins of the Business Analyst Core Concept Model (BACCM™) and Core Concepts. Now it's time for an overview of the Core Concepts, with a few highlights about key implications. We approach this discussion by further defining key words in the definition of each Core Concept. After this analysis—after we've broken it all down into tiny pieces—we will synthesize the concepts back into a coherent model.

While this is an overview, it still covers a lot of ground. You may want to take it in sections—one Core Concept at a time.

A. On the Nature and Structure of BACCM Definitions

Nature

The Business Analyst Core Concept Model was created using an empirical, behavioural approach.

- Empirical: We looked for evidence to describe each Core Concept, and then reasoned from that evidence to create simple, useful definitions.

- Behavioural: Definitions focus on the best available evidence about actual human behaviour, rather than philosophical, moral, ethical, or economic beliefs about our behaviour.

This approach was particularly important when defining need, solution, and value. Review and analysis of available literature made it clear that oversimplifications of human behaviour result in overcomplicated models. Errors and misrepresentations result in models that cannot account for common situations.

Structure

Each definition is phrased as a sentence fragment that can be copied directly into another sentence to replace the word it defines. This approach allows for some powerful analysis, particularly since each Core Concept is defined in terms of all six Core Concepts. In a future article, we will do some of this analysis, but you can try it yourself with the definitions below.

The interconnected nature of these concepts has another implication for the definitions: they could all be unusably long. The Core Team chose to focus the definitions on a short, clear phrase that captures the essence of the concept. In some cases we added a short explanatory clause to provide additional direction and context for this main clause. For example, it is valid to state that a need is "a problem, opportunity, or constraint"—but it is often helpful to note that each need has "potential value to a stakeholder". It is also correct to state that a need is "a problem, opportunity, or constraint with potential value that could be realized by a stakeholder in a context though a change that delivers a solution". Unfortunately, "correct" is not the same as "useful", so shorter, focussed definitions were chosen.

2.0 Analysis

.1 Change - a controlled transformation of an organization

Change is the Core Concept with the most specialized definition in the model. The common use of the term includes many kinds of change that are not usually the subject of business analysis work. For example, personal or individual change is usually the realm of psychology. The work of turning raw materials into finished products is also a kind of change—it is the actual operation of the organization—but BAs do not work on the assembly line. BAs don't operate the organization; they help change the way the organization operates.

This means business analysis is performed for one primary reason: to improve organizational performance by controlling change to organizational capabilities. To understand change from a BA point of view, you have to understand two terms in the BACCM definition of change:

-

Organization: A collection of stakeholders acting in a coordinated manner, and in service to a common goal. "Organization" includes the private and public sectors, from governments to religions to corporations to militaries to charities. "Enterprise" is also used in this way.

-

Control: Conscious attention is paid to directly effecting the change, by provoking it, preparing for it, or preventing it. For example, business analysis is not concerned with controlling earthquakes, but it is concerned with controlling the organizational capacity to respond to them, and to controlling the consequences.

We mentioned three categories of control over change exerted by BAs:

-

Prepare Change. What is changing? What is the context for that change? Who cares about the change? Why? BAs ask these kinds of questions as a foundation for managing stakeholders, setting expectations, understanding scope, and making good decisions.

-

Provoke Change. Each change causes a mixture of increases and decreases in value: this solution option costs more to buy; that solution option takes longer to implement; another solution option benefits one stakeholder but harms another. BAs discover and define potential changes to understand which ones are most likely to be most beneficial. We explore boundaries; we discover problems, opportunities, and constraints; we represent these needs in ways that promote action.

-

Prevent Change. For potential changes that are likely to decrease value, BAs are positively negative. We do our best to get damaging change prioritized to the bottom of the queue, to invalidate bad business cases, to uncover false assumptions, and to question questionable decisions. We also work to ensure the organization has the capability to control itself day-to-day, through meaningful reporting.Good reports help management put a stop to undesirable changes, like increases in product defects, or decreases in sales.

Change is a complex, recursive, fractal concept—so business analysis is too.

.2 Need - a problem, opportunity or constraint with potential value to a stakeholder

Need and change are entwined. Needs can cause changes by motivating stakeholders to act—to seek some purpose, or to collect some benefits. Changes can also cause needs—problems, opportunities, or constraints—by eroding or enhancing the value delivered by existing solutions. In many cases Business Analysis work begins with needs, and needs always guide Business Analyst work. A Need (like a solution and value) is an experience that a stakeholder has, and not a thing in itself. A need can only exist if there is a person to have it. The potential value of a need is discussed in more detail in the section on value.

BAs must be careful to educate their stakeholders on a key characteristic of needs: sometimes, they are not met. Even the most basic needs, for air, for water, for food, for shelter, for love, for meaning—these needs sometimes go unfulfilled.

A. Problem, Opportunity, Constraint

"Problem" and "opportunity" are often used to talk about needs, and for most of us they feel like a natural part of the definition of the concept. These ideas encompass the first part of the definition of a requirement in A Guide to the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge ® (BABOK® Guide):

1) A condition or capability needed by a stakeholder to solve a problem or achieve an objective.

In the BACCM, a constraint is something that limits your options. This is often positive: a solid, stable foundation is a constraint that makes it possible to build a solid, stable structure. It can be negative too: a federal regulation might make it illegal for your organization to share customer information across divisions, making it hard to provide good customer service experiences. In this sense, "constraint" encompasses the second part of the definition of a requirement in the BABOK®Guide:

2) A condition or capability that must be met or possessed by a solution or solution component to satisfy a contract, standard, specification, or other formally imposed documents."

This idea is fairly broad. Some constraints—like seasons and lifespans—are not 'imposed' by a stakeholder.

Thinking of constraints in this way may feel unfamiliar or forced, particularly since the term has a special, unrealistic definition in the IT project management world. Discussion of the relationships among Constraints, Assumptions, Risks, Requirements, and Dependencies (CARRDs) will be the subject of the next article in this series.

B. Needs and Requirements

The BACCM defines a requirement as "a usable representation of a need". (Try substituting the definition of 'need' into this definition. Does it make sense? What other substitutions can you make?) We'll dig into this definition in a future article called "Needs and Solutions, Requirements and Designs", but for now it is important to recognize that needs and requirements are not the same thing. A need may exist without being recognized, understood, expressed, or acted on. A requirement is an expression of a need, so there is no such thing as an 'unexpressed requirement'.

A requirement defines the potential value associated with a need, and represents the need so it can be acted on. Requirements may be found on the back of a napkin, in a Business Requirements Document, or in a storyboard. In each case some need is represented in a way that a specific stakeholder can use.

This is the general case of the third part of the definition of a requirement in BABOK® Guide:

3) A documented representation of a condition or capability as in (1) or (2).

C. Who Has Needs

Needs represent something with potential value to a stakeholder, so a need cannot be understood until the stakeholder is identified. By definition, all controlled organizational changes have three categories of special stakeholders:

-

The organization has needs that set the overall scope and direction of any operations and any change. These needs are often identified as goals, targets, objectives, directions, and so on.

-

Change Agents are people changing the organization. They have needs related to making that change.

-

Change Targets are people being changed. They have needs related to a functioning solution.

One person may fit into more than one category, and other stakeholders may have needs of various sorts—often related to one of the Core Concepts—but these groups are a good place to start.

D. Needs and Solutions

"I need" may be an interesting philosophical statement, but the phrase only has practical meaning when it is applied to something: "I need something." The thing needed is also known as a solution.

Needs and solutions are concepts that cannot be separated, in the same sense that north and south magnetic poles cannot be separated. You can recognize one at a time, analyse its characteristics, and show that they are different—and yet it is impossible to discuss one without the other.

There are deep reasons for the inseparable nature of these concepts, rooted in value, contexts, and stakeholders. When we get to the discussion of solutions, below, we'll use an example that shows a single object to be a need and a solution at the same time. This will also be the subject of a future article, called "Needs and Solutions, Requirements and Designs".

.3 Stakeholder

a group or individual with a relationship to the change or the solution

This Core Concept may be the most 'jargony' and also the simplest to understand. The BACCM definition is a generalized version of similar definitions used by other organizations. For example, PMI defines stakeholders in terms of interest and influence over the change. The BACCM considers 'interest' and 'influence' to be two of many kinds of relationships that a stakeholder might have with the Core Concepts. The definition focuses on these Core Concepts because it is usually practical to look to the change or the solution as the primary relationship a stakeholder cares about. For example, people often care about relationships with other people more than they care about the change or the solution, but the BA can probably analyse these relationships in terms of the change or the solution.

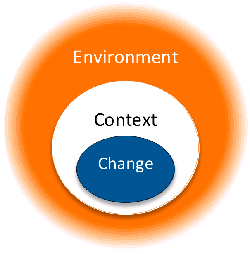

.4 Context - the part of the environment which encompasses the change

Changes occur in a context—those parts of the environment that are relevant to the change. A context has two boundaries:

-

the inner boundary defines the scope of the change.

-

the outer boundary defines the scope of the things relevant to the change, separating them from the environment.

In other words, the context is everything relevant to the change, but not the change itself. It may include almost anything: attitudes, behaviours, beliefs, competitors, culture, demographics, goals, governments, infrastructure, languages, losses, processes, products, projects, sales, seasons, terminology, technology, weather, or any other element meeting the definition.

The context is distinct from the controlled organizational change, but that does not mean it is static. For example, the cyclical change of the seasons is relevant to many product launches, and the movement of the planets was important to the Mars Curiosity Rover mission.

In practice, a context provides a common way for stakeholders to talk about their relationships to the change and solution, and to define what is relevant. Most organizational change requires many stakeholders to work together fairly seamlessly despite working in different personal contexts. For example, a stakeholder who will use a bridge when it is built doesn't really care what engineering software was used to model the bridge; the engineer and the driver have different contexts. For the Business Analyst, these are both relevant.

Controlling the scope of the context (and as a result, the scope of the change) is one of the most important services that BAs provide. Remember, the context defines what is relevant to the change but not part of the change. In the example above, the BA does not control the modelling software itself; the Business Analyst determines whether it is relevant to the change or not (in context, or part of the environment).

The term 'situation' is useful for referring to the combination of the context and the change it contains. In the BACCM it is explicitly defined as 'context + change = situation'. Common use is very similar.

.5 Solution - a specific way of satisfying a need in a context

Solutions satisfy a need—an idea with potential value—by realizing, delivering, exchanging, storing, or creating value. Solutions may not be tangible, but they are always a combination of a stakeholder experience of value and a thing the value is associated with. For example, a chair can be used as a seat, status symbol, bed, footstool, fuel, door-lock, barrier, or weapon, depending on what the stakeholder needs in the current context. In each case, a stakeholder experiences some value associated with chair.

A. Solutions and Needs

In normal conversation, a thing is only called a solution if a stakeholder can use it to deal with a problem, opportunity, or constraint, in a context.

A solution satisfies a need by:

- resolving a problem faced by stakeholders,

- allowing stakeholders to take advantage of an opportunity,

- enforcing a constraint requested by stakeholders,

- permitting an activity by removing a constraint, or permitting activity within a constraint.

B. Solutions and Value

Solutions are valuable in some combination of the following three ways:

-

Functionality: The solution allows a stakeholder to do something that is otherwise difficult or impossible. The chair is a platform that holds a person some small distance over the ground.

-

Characteristics: The solution confers some characteristic on a stakeholder. A throne indicates a person has power, wealth, or both.

-

Experiences: The solution allows a stakeholder to experience something that others do not experience. The front-row-centre chair at the concert hall offers a different experience than the back-row-obstructed-view chair.

The iPhone is an example of a consumer product that is valuable primarily for the characteristics it confers to the owner; functionality and experiences are important, of course, but not to the same degree.

C. Solutions and Context

These definitions of solution seem to imply that value is an inherent or intrinsic property of an object, or even that value is a thing in itself. This simplification is useful in many circumstances, and is philosophically interesting, but it does not reflect the practical reality of how stakeholders relate to needs and solutions.

For example, consider a neighbourhood where a new electrical power station will be built. People outside the neighbourhood will also use the power generated by the new power station.

-

For some local residents, the power station may have high positive value: construction workers will have several years of good jobs.

-

For other locals it has high negative value: the local officials responsible for public health get pollution (poisonous, radioactive coal smoke).

-

For non-residents outside the neighbourhood, the power station has some positive value: such as lower prices and more reliable service.

This example tells us that the value associated with a solution depends on

-

the stakeholder (construction worker vs. health official), and

-

the context (my neighbourhood vs. non-resident).

Each of these stakeholders sees the same thing as having different value. For local construction workers it is a solution to work towards, but for local health officials it is a problem to prevent (actually a type of need).

The Business Analyst Core Concept Model helps us understand and resolve longstanding problems such as the "Paradox of Value" by taking a practical, subjective view of value. The BACCM acknowledges that needs, solutions, and value cannot be defined in absolute terms, and can only be understood relative to a stakeholder in a context. (See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paradox_of_value for more information about the paradox of value, and on marginalism.)

The relationship between the price of a solution and the value of a solution will be discussed in detail in a future article, but see the section on value for a summary.

D. Solutions after Change: The New Context

A change is complete when a solution is implemented and is delivering value: the stakeholders' needs have been fulfilled. When this happens, the thing that we called a 'solution' is no longer a goal to strive for; it is part of the normal operations of the organization. In other words, the thing we called a 'solution' before has become part of the environment. In many cases it will be relevant to new organizational changes; when this is the case the 'solution' becomes part of a new context.

All organizations have many of these existing solutions to existing needs—a called infrastructure.

.6 Value - the importance of something to a stakeholder in a context

Outside of dense tomes of philosophical and economic lore, value is not clearly defined. It is used everywhere in business texts, but the authors generally assume that everyone knows what value is, and that we agree on that definition. Consider that this article first describes some characteristics of value in the "Solutions and Value" section of Change, above. It probably didn't bother you that it was used 19 times over more than 2500 words before that section, or that it was used 35 times before the formal definition was presented (now over 3000 words in).

This lack of definition was a significant problem during the development of the Business Analyst Core Concept Model, and was the subject of many intense debates. In keeping with our empirical, behavioural approach to the model, we reviewed some evidence scientists have collected, relating how our brains assess value, and how we behave when making decisions of value. In the end, we realized that the dictionary had the simplest, clearest definition of value (buried among the definitions that can be reduced to "value = money"):

"the importance or significance of a thing"

As discussed in the section on solutions, value depends on the context and the stakeholder. The BACCM states this directly by adding "...to a stakeholder in a context."

When considered with the rest of the Core Concepts, "the importance of something to a stakeholder in a context" encompasses both the common use of the term and the otherwise undefined meaning used in business.

A. Importance, Ranking, and Prioritization

Value is a measure. In some cases, value can be assessed in absolute terms. For example, if one device has 16GB of storage, and another has 64GB of storage, the second device is probably more valuable to most stakeholders. In many cases, value is assessed in relative terms. I cannot put a number on how much I love my mother, or my wife, or my daughter—but I can tell you who I would pull out of a burning building first, and second, and third. I could also tell you whose dinner I would choose first, and second, and third; the context changes how I rank or prioritize each person.

Value is assessed based on many contextual factors. For example, urgency is a measure of importance with respect to time, while ROI is a measure of importance with respect to a balance sheet. Every decision that involves sequencing, ranking, prioritizing, or scope involves analysis of value at some level.

B. Motivation and Reward

Value has two major elements. On one hand, value is used to describe the benefits that will result from some action. For example, remuneration—getting paid—is a benefit of working for someone. On the other hand, value is used to describe the motivations that provoke a person to act in the first place. For example, the experience of having an effect on the world—to feel useful—is a powerful motivation to work. IIBA exists because of this motive: volunteers work to make a difference.

C. Money and Value

Money is one narrow measure of one kind of value. It can dangerously oversimplify assessments of value, provoke irrational decisions, and corrupt our sense of what is fair. It is also enormously useful, and a necessary part of almost everything an organization does.

IIBA has published several articles that explore the nature of value in great detail in the series "Future of Business in the Internet Economy", Part 1: Scarcity – the Great Motivator, Part 2: Free – the Disruptive Price, Part 3: Value Analysis and Part 4: The Abundant Business Case. These include discussions of what kinds of value can be exchanged for money, and those that cannot. Future articles will build on these ideas. One of the first will be called, "Positive Debt: Gifts and Familial Value."

3.0 Synthesis

What you have read so far is a brief overview of 14 months of investigation, discussion, and debate with passing reference to the implications of the Business Analyst Core Concept Model on a few key BA terms, such as plan, risk, requirement, design, motivation, benefit, environment, and situation. At this point it should be clear that the BACCM is a rich source of insight, despite its simple set of six Core Concepts.

The definition of 'change' in the BACCMs more constrained than common use. This keeps the model focussed on Business Analysis. The definition of 'value' is as broad as common use. This extends the domain of the profession to any realm where an organization attempts to control change. It makes it possible to describe business analysis as the practice of enabling change in an organizational context by defining needs and recommending solutions that deliver value to stakeholders.

While this is an abstract, conceptual model, it is also a deeply practical one. It can be used to make predictions about the way stakeholders will behave, uncover unexpected needs, and evaluate solutions in a meaningful context.

As you go about your normal tasks, try to describe the work you are doing in terms of the Core Concepts. For example, if you are developing a use case, consider questions like:

-

Where do I describe the context for the process?

-

How is value described?

-

Who cares about that value?

-

Is that stakeholder motivated or rewarded by this value?

Using these terms in your normal work discussions will help you internalize the Core Concepts and the Business Analyst Core Concept Model itself. It doesn't take long for these ideas to become a natural part of your thinking, informing all your work.

A. A Final (Fun) Thought

While all six Core Concepts are equally important, they are not equally understood, or equally understandable. This article reflects this in the frequency of the use of each term. Of the 4000 words in the main body of the article, they appear as follows:

Core Concept / Count / % of Article

Value - 68 - 1.700%

Change - 65 / 1.625%

Stakeholder - 63 / 1.575%

Need - 57 / 1.425%

Solution - 54 / 1.350%

Context - 36 / 0.900%

Total - 343 / 8.575%