The Process of Decision Making

Editor’s note: The benefit of creating a process is that you can use it over and over again to ensure consistent outcomes. This article was first published in The Global BA blog.

Making a Decision

One of my early mentors said to me "You don't have a decision until you have options." Along with "Your most strategic decision will be the one where you have the hardest choice to make", that's always lived with me.

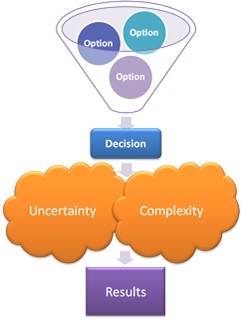

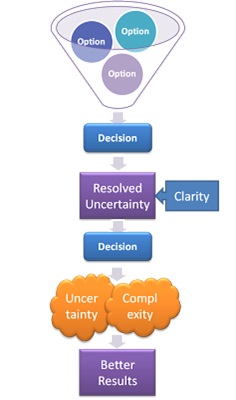

We live in a world of imperfect information and even our most informed decisions are going to be realized within a framework of uncertainty and complexity.

To make quality decisions, we need to do it within a framework where we can raise the amount of certainty that the result is a good one. Having a repeatable process for making decisions won't guarantee good outcomes, but it can give us more confidence that we will get to a better outcome.

People Make Decisions

One of my common refrains is that as analysts, we fundamentally misunderstand how others make decisions. It's natural for us to approach a decision as:

Our process could be summarized as(1):

1. Define the problem, characterizing the general purpose of your decision.

2. Identify the criteria, specifying the goals or objectives that you want to be able to accomplish.

3. Weight the criteria, deciding the relative importance of the goals.

4. Generate alternatives, identifying possible courses of action that might accomplish your various goals.

5. Rate each alternative on each criterion, assessing the extent to which each action would accomplish each goal.

6. Compute the optimal decision, evaluating each alternative by multiplying the expected effectiveness of each alternative with respect to a criterion times the weight of the criterion, then adding up the expected value of the alternative with respect to all criteria.

The reality is that people who aren't trained as analysts tend to make decisions within the following context:

All of your analysis and data doesn't matter in an emotional decision! (For more see Dan Areily; Predictably Irrational)

Taking this into account, according to Thagard(1), we can make our decision making process stronger by incorporating intuition (emotion) into it:

Set up the decision problem carefully. This requires identifying the goals to be accomplished by your decision and specifying the broad range of possible actions that might accomplish those goals.

Reflect on the importance of the different goals. Such reflection will be more emotional and intuitive than just putting a numerical weight on them, but should help you to be more aware of what you care about in the current decision situation. Identify goals whose importance may be exaggerated because of jonesing or other emotional distortions.

Examine beliefs about the extent to which various actions would facilitate the different goals. Are these beliefs based on good evidence? If not, revise them.

Make your intuitive judgment about the best action to perform, monitoring your emotional reaction to different options. Run your decision past other people to see if it seems reasonable to them.

Making Bad Decisions

When we do get more information, oftentimes we find that our decision could have been better. Rationally then, we should use the greater clarity from that information to continue to refine towards better results.

Unfortunately, due to a phenomena called “loss aversion”*, we will often not factor the sunk costs as lost resources but as a greater impetus to continue down the same path that we embarked on.

The good folks at Psychology Today have some pointers on how to avoid the escalation of commitment to a losing course of action:

- Separate the initial decision-maker from the decision evaluator. Once you’ve made the initial choice to go to the restaurant or hire the employee, you’re no longer in a neutral position to decide whether to keep investing in that course of action.

- Create accountability for decision processes, not only outcomes. Many leaders like the idea of holding people accountable for the results they achieve. That way, employees have the freedom to choose different methods and strategies, and we don’t have to monitor their work along the way. The problem with this approach is that it allows employees to make faulty decisions along the way, convincing themselves that the ends will justify the means. Essentially, having people explain and defend how they will come to the decision will allow them to make decisions that are not as strongly influenced by emotion and they will be in a better position to analyze their options. In having accountability for the process of making the decision, you are pre-loading business rules into the decision and setting triggers for the points that the decision maker can exit the decision process.

- Shift attention away from the self. Once you’ve learned that an initial choice didn’t pan out, your focus immediately turns to your pride and your reputation. Research shows that if you consider the implications of the decision for others, you can make a more balanced assessment.

(1) Using Intuition and Emotion to Make Good Decisions

*Think about the last time you finished a book or a movie that you really weren't enjoying. You put a lot of effort into that endeavor so far and you sure wouldn't want to waste it would you? The reality is, the time and resources you used to that point are already gone.